St Mary Magdalene, Crowmarsh Gifford

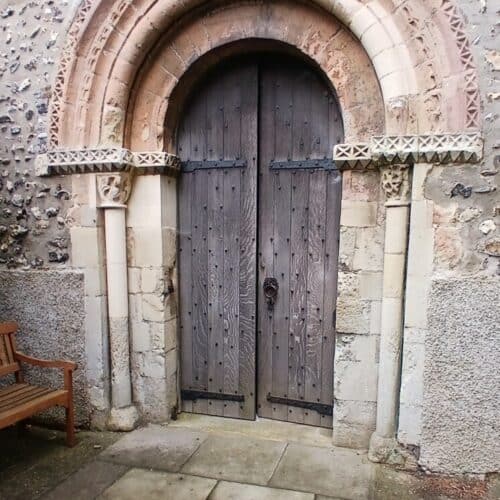

A Norman church restored in the nineteenth century, with a west door that proclaims its early history. A second blocked-up Norman doorway can be seen on the south wall of the nave, and there are two early oculi set high in the west wall.

The chancel has two memorials that interested me. The first is a stone tablet of the seventeenth century commemorating Bridget Parsons, who ‘changed earth for Heaven’ in 1645: ‘Who reads the legends of the former ages/’St Bridgets Praise’, may find in sundrie pages/Popes, poets, painters have both power and skill/To canonize, praise, paint what saints they will./Such vaine helps doth not Bridgit Parsons need/Whose life, and death, proved her a saint indeed./Then cease, vaine teares, make noe fruitles complaint./The earth hath lost, now Heaven injoyes this saint.’ 1645 was the first year of the Civil War; I’m inclined to feel from the dismissal of the ‘vaine helps’ specified that Bridget and her family may well have inclined to a Puritan custom and practice.

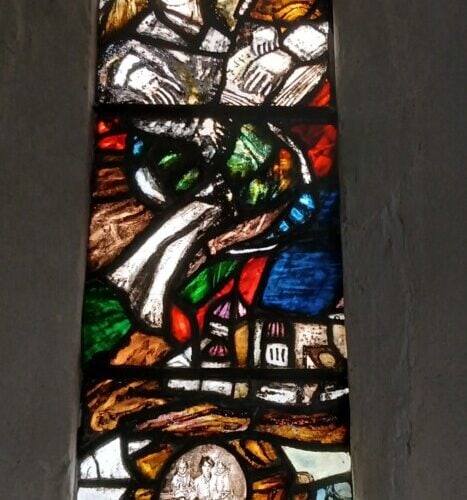

I was rather taken, too, by a later memorial: a 1961 stained glass window put up by Frank Wilder in memory of his wife Emily (1881-1955). It is apparently by Charles de Vic Carey, and in the lower light has an inset medallion depicting her with (presumably) her two children.

St Mary’s, Newnham Murren (Churches Conservation Trust)

A small flint-built, red-roofed church dating from the twelfth century, but restored (Pevsner says

that the lancet windows at the east end were ‘drastically renewed’) in 1849. The bellcote at the west end of the church was put up at the same time. Once a dependent chapel of North Stoke, Newnham Murren today is another church in the care of the CCT. Enter through the north door (via a Victorian porch), and look east to see a high narrow chancel arch: the height of the chancel makes the nave seem shorter than I think it really is.

To the right, there is a squint which is almost horseshoe-shaped, and through which you get a much focused view of the altar.

Newnham Murren was a dependent chapel of North Stoke for many centuries, and as a parish can never have had a large congregation, but it may have been all the more valued by its own community. It feels a very cared-for building today: the sense of welcome was added to by a large jug of yellow flowers in the porch. And, as with all churches, there are reminders of different centuries—one, in this case, recalling a time of violence. A brass memorial plaque on the south wall to Letitia Barnard, d. 1593, has a bullet hole in it, which

it is suggested dates from the Civil War, and the siege of Wallingford in 1646. (Did a Parliamentary trooper of iconoclastic turn of mind find the depiction of Letitia and her children idolatrous?)

St John the Baptist, Mongewell (Churches Conservation Trust)

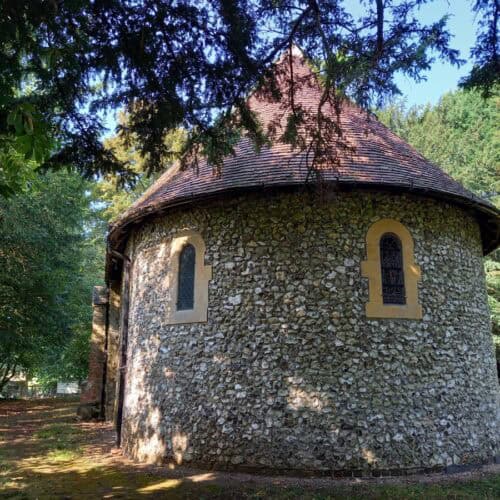

We have only a fragment of this church still standing, but it is well cared for by the CCT. It stands within the grounds of what was Carmel College, founded in 1948 near Newbury by Rabbi Dr Kopul Rosen, and established at Mongewell in 1963. The college closed a number of years ago, and the buildings are strictly off-limits to visitors (I rather regret that, I’d like to see what Pevsner describes as Thomas Hancock’s ‘spectacular and successful’ synagogue, and the amphitheatre). You make your way through the grounds, following a signed path, and finally come through the trees to see the rounded apse of St John’s.

In the 1930s St John’s was (just) viable as a functioning building; John Johnson, Printer to the University and a great visitor of churches, waged a vigorous if unsuccessful campaign to stop the roof of the nave (and the associated eighteenth century glass in the windows) being lost. He first appealed to the Rector of Henley and the Bishop of Oxford, and getting no satisfaction from them looked further afield for help. Mongewell is the burial-place of Shute Barrington (1734-1826), Bishop of Durham, and Johnson wrote to the then Dean of Durham, Cyril Alington, invoking Barrington’s name as a reason for Durham to provide help for what he described as ‘a gem with a Norman apse and at the other end a tiny tower in Strawberry Hill Gothic. There is nothing like it that I know’. The reference to the tower was particularly apposite, since it had been Shute Barrington himself (as owner of the manor) who was responsible for its existence (apparently the architect may have been James Wyatt). Pevsner tells us that the church was ‘remodelled in Gothic’ in 1791, and that the west apse and ‘battlemented polygonal turret’ were part of that.

Regrettably Johnson’s efforts came to nothing, and Mongewell’s state of disrepair continued; Pevsner saw it as a ‘romantic ruin, complete with tombs’, by which time the nave had completely lost its roof and was open to the sky. Today, however, things are better: the site is cared for, and the chancel (currently undergoing roof repairs) has had a door installed by the CCT to protect it from the elements.

It is possible to say that both Johnson and Pevsner were right: it was worth saving (and is most definitely worth conservation and care today), but it does make a ‘romantic’ ruin.

The church did undergo one more building phase after Barrington’s day, when the chancel was ‘Normanized’ in 1880, with zigzag decoration added. The memorials within the chancel, however, are testimony to the eighteenth century. There is an inscribed tablet to Barrington himself, which gives the key points of his career (‘Bishop of Llandaff 1769. Translated to Salisbury 1782 and Durham 1790’), and the essentials of his lineage—we learn that he as the sixth son of ‘John Barrington, First Viscount and Baron Barrington in the Kingdom of Ireland 1720’.

And Pevsner was also right to comment on the tombs. There is a wall tomb with two serious-looking busts, and a really notable tomb of 1731, with the figure of John Sanders shown as a ‘man of sensibility’ reclining on a sarcophagus, holding a book, and wrapped in elegant draperies.

St Mary’s, North Stoke

St Mary’s is Anglo-Saxon in origin, with a chancel rebuilt in the mid thirteenth century. It has an aisleless nave dating from the early fourteenth century, and a square west tower. A sundial above a blocked south doorway, consisting of a dial grasped in a pair of hands and surmounted by a head, may in an indication of the earliest part of its history, although BoE says that the head seems to be a thirteenth-century substitution for an original. The pulpit is Jacobean.

© John Ward

© John Ward

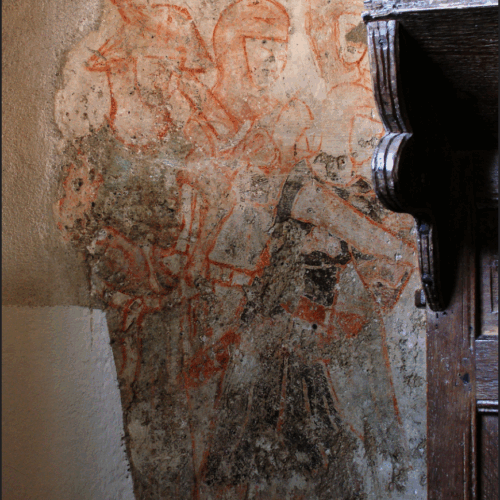

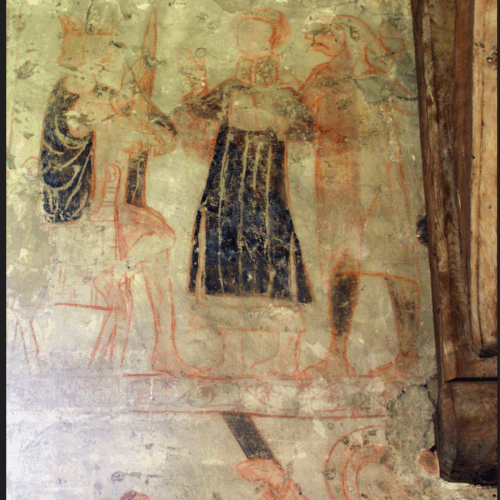

St Mary’s is notable for its wall paintings, dating from the mid fourteenth century. Subjects include the martyrdom of Thomas Becket (the heads of the four knights can be seen to the left of the pulpit), the life of St Stephen, and a Passion cycle. The legend of the Three Living and Three Dead kings is depicted over the north doorway.

© John Ward

© John Ward

© John Ward

St Mary’s has a unique feature; it is the only point on the whole of its route at which the Ridgeway actually runs through a churchyard.

By Elizabeth Knowles

About the Author

Elizabeth Knowles is a renowned library researcher and historical lexicographer who devoted three decades of her career to Oxford University Press. Her time at OUP began with contributions to the OED Supplement and the New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Subsequently, she spearheaded the Quotations publishing program, solidifying her reputation as a leading expert in quotations and lexicography.

In 1999, Knowles assumed the prestigious role of Editor of the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, a position she held continuously until her retirement from OUP in 2007. Under her editorial guidance, the eighth edition was published in 2014, marking a significant milestone in the dictionary’s history.

Knowles is a prolific writer and lecturer on the history of quotations and dictionaries. She has shared her extensive knowledge with both academic and general audiences, significantly enhancing our understanding of the role of quotations in language.

Beyond her work on the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, Knowles is also the editor of “What They Didn’t Say: A Book of Misquotations” (2006) and “How To Read a Word” (2010). Her work continues to inspire and inform scholars, writers, and readers fascinated by the English language.

All photographs © Elizabeth Knowles unless otherwise noted

Churches visited on this route