OHCT Trustee and leading architectural historian Professor Malcolm Airs, OBE, corrects the record for the impressive Dorchester Abbey lych-gate. The article which appeared in The Victorian, March 2022, is reproduced here with the kind permission of the Victorian Society.

Malcolm Airs comes to the rescue – and identifies the actual date and architect of the lych-gate that appears on the July 2021 cover.

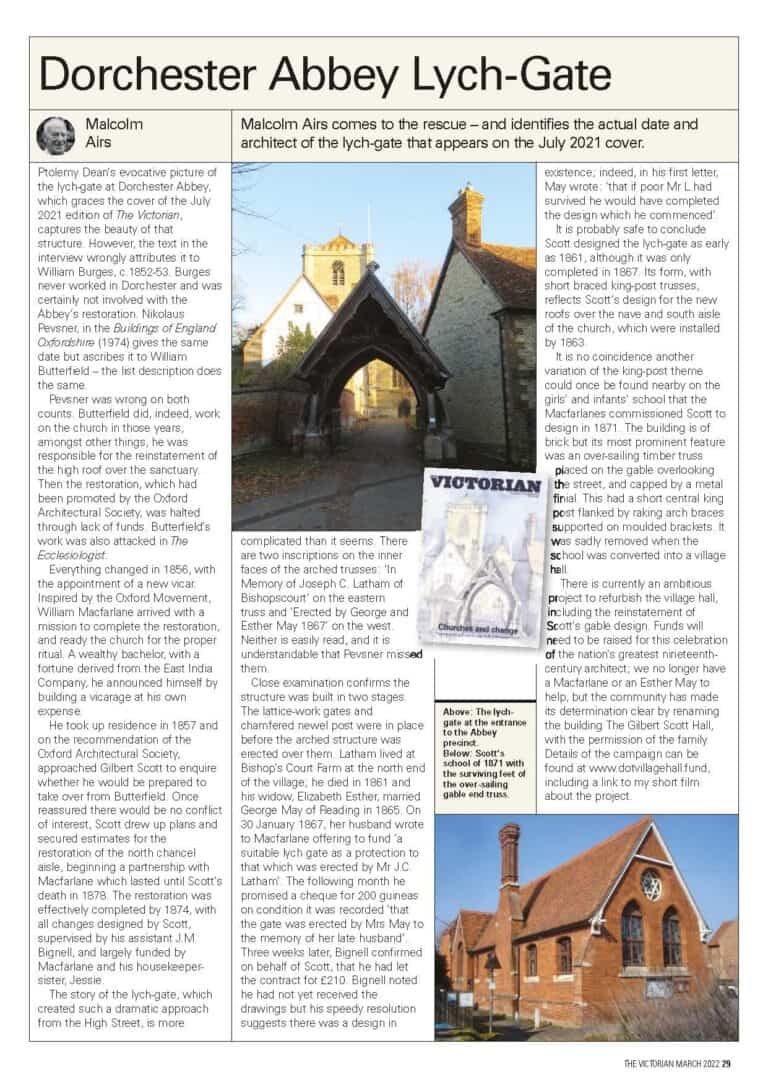

Ptolemy Dean’s evocative picture of the lych-gate at Dorchester Abbey, which graces the cover of the July 2021 edition of The Victorian, captures the beauty of that structure. However, the text in the interview wrongly attributes it to William Burges, c.1852-53. Burges never worked in Dorchester and was certainly not involved with the Abbey’s restoration. Nikolaus Pevsner, in the Buildings of England Oxfordshire (1974) gives the same date but ascribes it to William Butterfield – the list description does the same.

Pevsner was wrong on both counts. Butterfield did, indeed, work on the church in those years; amongst other things, he was

responsible for the reinstatement of the high roof over the sanctuary. Then the restoration, which had been promoted by the Oxford Architectural Society, was halted through lack of funds. Butterfield’s work was also attacked in The Ecclesiologist.

Everything changed in 1856, with the appointment of a new vicar. Inspired by the Oxford Movement, William Macfarlane arrived with a mission to complete the restoration, and ready the church for the proper ritual. A wealthy bachelor, with a fortune derived from the East India Company, he announced himself by building a vicarage at his own expense.

He took up residence in 1857 and on the recommendation of the Oxford Architectural Society, approached Gilbert Scott to enquire whether he would be prepared to take over from Butterfield. Once reassured there would be no conflict of interest, Scott drew up plans and secured estimates for the restoration of the north chancel aisle, beginning a partnership with Macfarlane which lasted until Scott’s death in 1878. The restoration was effectively completed by 1874, with all changes designed by Scott, supervised by his assistant J.M. Bignell, and largely funded by Macfarlane and his housekeepersister, Jessie.

The story of the lych-gate, which created such a dramatic approach from the High Street, is more complicated than it seems. There are two inscriptions on the inner faces of the arched trusses: ‘In Memory of Joseph C. Latham of Bishopscourt’ on the eastern truss and ‘Erected by George and Esther May 1867’ on the west. Neither is easily read, and it is understandable that Pevsner missed them.

Close examination confirms the structure was built in two stages. The lattice-work gates and chamfered newel post were in place before the arched structure was erected over them. Latham lived at Bishop’s Court Farm at the north end of the village; he died in 1861 and his widow, Elizabeth Esther, married George May of Reading in 1865. On 30 January 1867, her husband wrote to Macfarlane offering to fund ‘a suitable lych gate as a protection to that which was erected by Mr J.C. Latham’. The following month he promised a cheque for 200 guineas on condition it was recorded ‘that the gate was erected by Mrs May to the memory of her late husband’. Three weeks later, Bignell confirmed on behalf of Scott, that he had let the contract for £210. Bignell noted he had not yet received the drawings but his speedy resolution suggests there was a design in existence; indeed, in his first letter, May wrote: ‘that if poor Mr L had survived he would have completed the design which he commenced’.

It is probably safe to conclude Scott designed the lych-gate as early as 1861, although it was only completed in 1867. Its form, with short braced king-post trusses, reflects Scott’s design for the new roofs over the nave and south aisle of the church, which were installed by 1863.

It is no coincidence another variation of the king-post theme could once be found nearby on the girls’ and infants’ school that the Macfarlanes commissioned Scott to design in 1871. The building is of brick but its most prominent feature was an over-sailing timber truss placed on the gable overlooking the street, and capped by a metal finial. This had a short central king post flanked by raking arch braces supported on moulded brackets. It was sadly removed when the school was converted into a villagehall.

There is currently an ambitious project to refurbish the village hall, including the reinstatement of Scott’s gable design. Funds will need to be raised for this celebration of the nation’s greatest nineteenthcentury architect; we no longer have a Macfarlane or an Esther May to help, but the community has made its determination clear by renaming the building The Gilbert Scott Hall, with the permission of the family. Details of the campaign can be found at www.dotvillagehall.fund, including a link to my short film about the project.