St Mary’s Church, Banbury

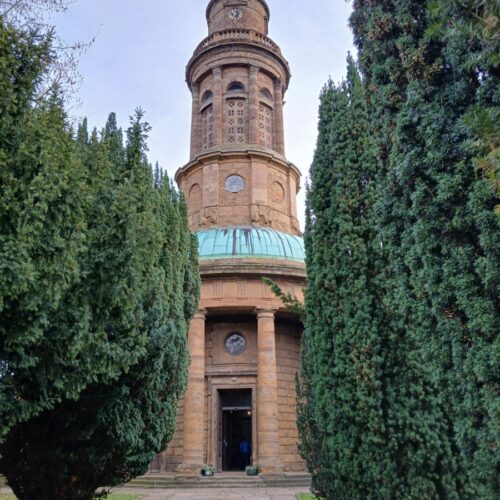

There was once a large medieval church here, but by the late eighteenth century it was apparently ‘ruinous’, and was replaced by the current structure, consecrated (before completion) in 1797. The architect was Samuel Pepys Cockerell (1753-1827), a great-nephew of the diarist. He was surveyor to the East India Company, and designed the notable Indian-style manor of Sezincote for his brother Charles, as well as Daylesford for Warren Hastings. The church was completed in 1818-22 by Cockerell’s son, who apparently slightly modified his father’s original plan when he added a semi-circular portico, and cylindrical west tower topped by a copper half-dome which, rising above now well-grown trees, are the visitor’s first sight of St Mary’s.

Cockerell’s design seems not to have been received with great warmth. Buildings of England quotes the Gentleman’s Magazine of 1800 characterizing it as ‘more like a gaol than a Christian temple’, and in 1840 John Henry Parker, writer on architecture and publisher, called it ‘despicable’. Parker was a supporter of the Oxford Movement, and would presumably have been encouraged by the significant interior remodelling of the 1860s, through what Nicola Coldstream in Oxfordshire Churches calls ‘the forceful intervention’ of the then Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce, the vicar Henry Back, and the architect Arthur Blomfield. As a result, the original ‘auditory’ Georgian interior was significantly modified bring the altar and sanctuary into central focus. The 1860s scheme laid great emphasis on the visual, including sequences of fine stained glass installed by the firm Heaton, Butler & Bayne. (According to Coldstream, a number of the designs were the work of a talented designer, Alfred Hassam, who died in 1869 at the age of twenty-six: on the evidence of St Mary’s, he was a considerable loss to his art.

Today when you walk up the portico steps and into St Mary’s, the impression is one of light, space, and colour. Samuel Pepys Cockerell’s original square space, punctuated by columns rising to a vault and with capitals picked out in red and gold, now terminates naturally at the east end in a flight of steps leading up to Blomfield’s raised sanctuary and apse, with paintings imitative of mosaics seen in early Christian churches.

The stained glass in the south and north aisles offer a range of striking illustrations of parables, some with an unusual focus. The Prodigal Son, rather than focusing on the son gloomily sitting among swine and husks, has his welcoming father as its central figure. Another window shows the parable of Hidden Treasure (Matthew 13:44-46).

Before the 1860s work, there was a gallery which ran round all four sides of the central square, and the south, west, and north sides still survive. Today, rather than offering maximum accommodation

for a congregation to hear a preacher, what strikes you about the gallery is the perspective it offers on the interior, and the ability to look at close quarters at the red and gold capitals at the top of the pillar.

The stained glass in the upper register also repays study, with scenes from the life of Christ set in central medallions flanked by illustrations of flora and fauna. One instance, in the north gallery, is particularly notable. Known as the ‘Arctic Window’, it commemorates Admiral Sir George Back (1796-1878), naval officer and explorer, who mapped a good deal of the Arctic. His nephew was Vicar of St Mary’s. The central medallions are in this case flanked by representations of sketches in Back’s journals: his ship Terror stuck in the ice, dogs pulling a sled, a group of walrus.

St Mary’s deserves a good deal of time and attention. Its remodelling to reflect contemporary ideas about liturgy, worship, and community use also make it particularly interesting in terms of church history. (Blomfield’s choir, which projected into the nave, was according to BoE removed in 2004 ‘to create a community theatre space.) It is a fine example of a sacred space that has adapted itself to contemporary needs while maintaining a core, and very pleasing, identity.

Quaker Meeting House

An oblong two-storey Ironstone building, dated to 1851, with a later (c. 1861) Tuscan porch in the south-west corner. This is a building with echoes of different periods in its life; the linked schoolroom (1906) has parts of the north and west walls of what was once (1681) the ‘women’s meeting room’, which in turn had been an extension of the original 1665 meeting house (now demolished).

The People’s Church (Baptist)

A late-twentieth-century brick-built church by G. Forsyth-Lawson, 1971-2. It is set endwise-on to the approach from Horse Fair, and the gable-ends follow a Gothic design. It stands on the site of a mid-nineteenth-century Unitarian chapel, and was the successor to the original Particular Baptist Chapel in Bridge Street.

St John the Evangelist, Roman Catholic Church

Built 1835-8 by Hickman and Derick, St John’s was designed in the Gothic Revival style, with a tall pinnacled west tower. (The pinnacles seen today are apparently renewals of the originals.) Inside it has a broad nave, and an chancel with a three-sided apse added by Pugin in 1840-1. Its painted interior decoration is much later, dating from the 1930s, as does the altar of Bath stone. BoE notes that the much earlier (fourteenth or fifteenth century) inset stone relief of the Crucifixion may have come from the old parish church.

(Wesleyan) Methodist Chapel

A substantial mid-nineteenth-century building, of rock-faced Brackley stone with Bath dressings, with traceried windows in the style of the late thirteenth century, and at the west end a porch surmounted by a tower and spire. The interior originally had galleries, but these were removed in a reordering of 1975 when a new glazed porch was also added. There are also two stained-glass windows of the 1920s which BoE attributes to Percy C. Bacon.

By Elizabeth Knowles

About the Author

Elizabeth Knowles is a renowned library researcher and historical lexicographer who devoted three decades of her career to Oxford University Press. Her time at OUP began with contributions to the OED Supplement and the New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Subsequently, she spearheaded the Quotations publishing program, solidifying her reputation as a leading expert in quotations and lexicography.

In 1999, Knowles assumed the prestigious role of Editor of the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, a position she held continuously until her retirement from OUP in 2007. Under her editorial guidance, the eighth edition was published in 2014, marking a significant milestone in the dictionary’s history.

Knowles is a prolific writer and lecturer on the history of quotations and dictionaries. She has shared her extensive knowledge with both academic and general audiences, significantly enhancing our understanding of the role of quotations in language.

Beyond her work on the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, Knowles is also the editor of “What They Didn’t Say: A Book of Misquotations” (2006) and “How To Read a Word” (2010). Her work continues to inspire and inform scholars, writers, and readers fascinated by the English language.

All photographs © Elizabeth Knowles unless otherwise noted

Churches visited on this route