St Peter’s Hanwell

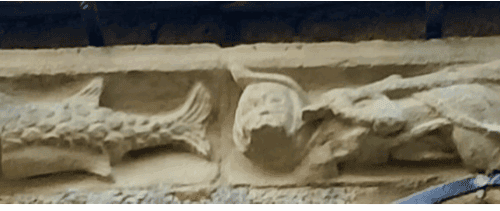

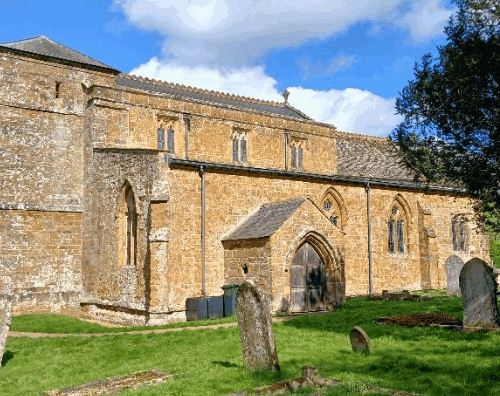

Approaching from the south, you see the church sideways on: a handsome Ironstone building, with a small turret on the west tower, and a wonderful frieze of animals and grotesques by local North Oxfordshire masons adorning the chancel.

When you have taken time to look at them, walk round the west end to enter the church by the north door (the village side).

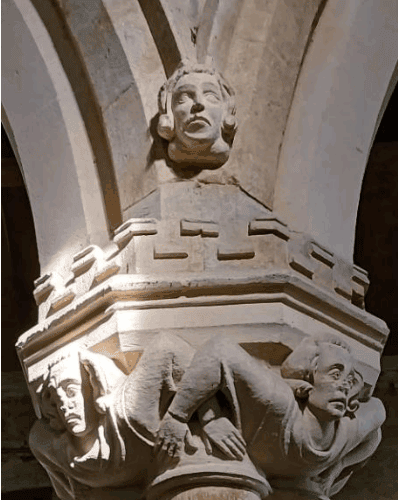

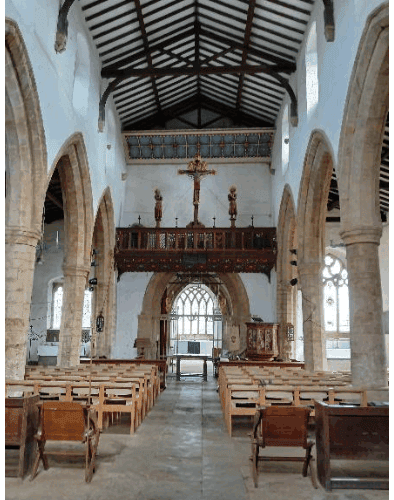

Inside it is a spacious building with aisles marked by three bays of arcades. The capitals are distinctive, showing men and women with linked arms (a design found in other churches in this region). The figures on the north side are slightly larger, and Buildings of England suggests that they are earlier. On the south side, there are minstrels carved standing above the capitals.

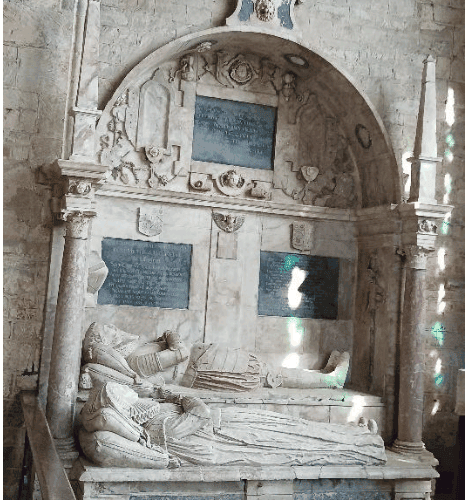

The effect is astonishing when you first step in, and if anything becomes more impressive as you take in the details. All this speaks to Hanwell’s rich medieval heritage, but before you leave go up into the chancel to admire the tomb of Sir Anthony Cope of Hanwell Hall (d. 1614) and his wife. You feel that no expense was spared.

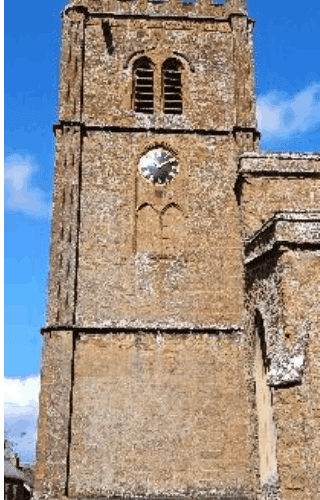

St Etheldreda’s, Horley

A fine early building; BoE says that the chancel and central tower are Late Norman ‘although much remodelled’. The nave was rebuilt in the thirteenth century and has north and south arcades of tall slender piers that are alternately round and octagonal. The fixtures and furnishings include a Norman aumbry and piscina in the chancel, a Gothic Revival pulpit of 1836 painted with scenes from the life of St Etheldreda, and an impressive mid-twentieth-century rood screen designed by T. Lawrence Dale, for many years Oxford Diocesan Surveyor, and architect of St Michael and All Angels, New Marston as well as other Oxfordshire churches.

However, the most striking feature of St Etheldreda’s is the marvellous fifteenth-century wall painting of St Christopher by the north door. It shows the saint fording a stream against a flowery background, with anglers on either side dangling hopeful lines for clearly delineated fish.

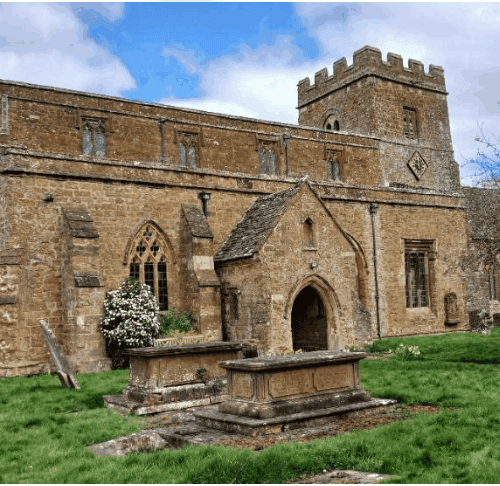

All Saints, Wroxton

This is another fine Ironstone church (on a sunny day, the stone glows red-gold against a blue sky). It is mainly from the early fourteenth century, with a fifteenth-century clerestory, other than the west tower. This was rebuilt in 1748; the architect, Sanderson Miller, is described by BoE as ‘gentleman architect, Gothic Revival pioneer, and squire of the nearby Radway Grange in Warwickshire’. Apparently it was originally surmounted by an octagon, which fell down in the first winter and was not replaced.

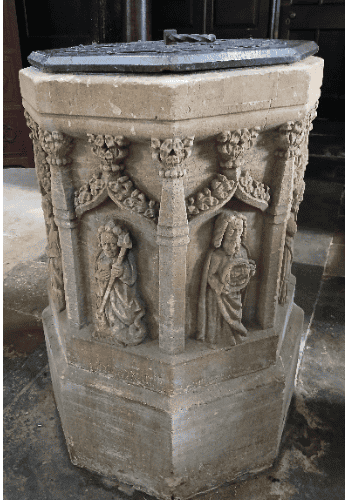

Inside there is plenty to see, including a notable fourteenth-century font with figures of saints (recut 1845-6); perhaps the most memorable features, though, are the memorials. All Saints stands opposite to the grounds of Wroxton Abbey, originally an Augustinian priory, but later the home of the Pope and then the North families. They are commemorated with appropriately grand effigies and memorials. William Pope, first Earl of Downe, d. 1631, and his wife lie on their tomb chest in the north-east corner of the sanctuary, with two respectful sons praying at their head, and their daughter at their feet.

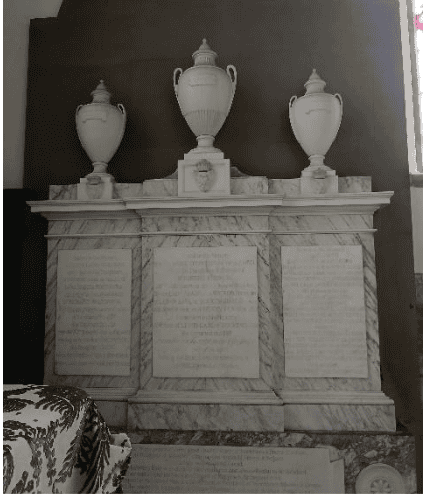

From a later period (1783), the three wives of Francis North, first Earl of Guilford, Lucy, Catherine,

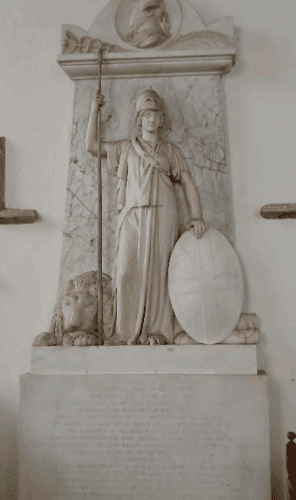

and Elizabeth have each a labelled urn on their wall monumbent of grey and white marble. It was the first Lady Guilford, Lucy, who was the mother of Frederick, eventually second Earl of Guilford but better known to history as ‘Lord North’, Prime Minister at the time of the American War of Independence. Despite what must have been seen as a lack of military and political success he is commemorated assertively by a figure of Britannia, spear in hand and lion at her side.

St Thomas of Canterbury, Wroxton

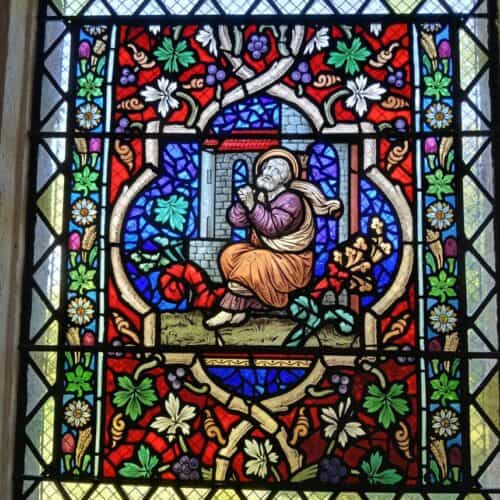

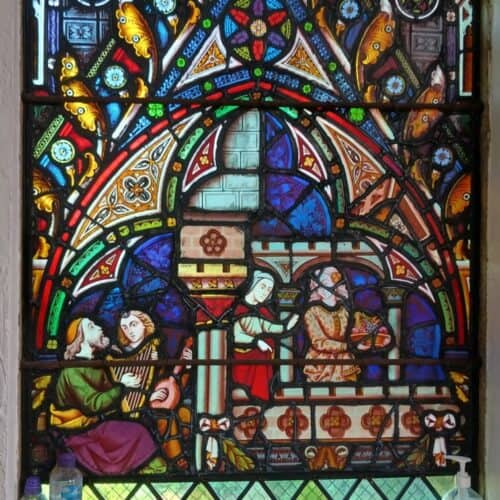

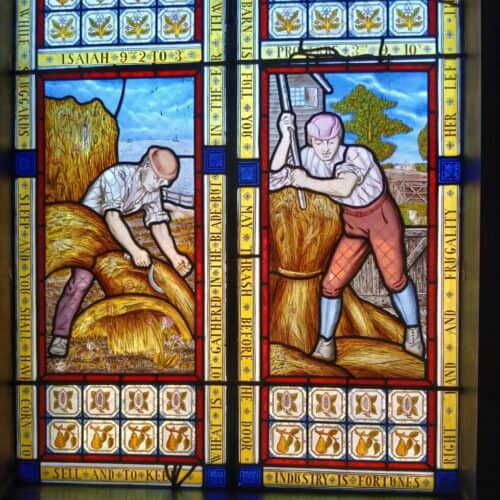

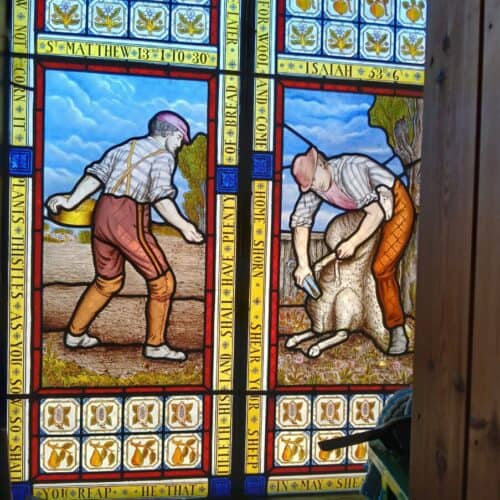

St Thomas of Canterbury, Wroxton is a small roughcast building with a thatched roof, bellcote, and porch at the west end. It is distinctive in being the only thatched church in Oxfordshire; it also represents a significant moment in English ecclesiastical history. In 1868 William North, the future eleventh Baron in succession to his mother, converted to Catholicism. He inherited the title and Wroxton Abbey in 1884, and three years later Wroxton’s first Roman Catholic church was erected on this site. It was a small building of corrugated iron which was largely replaced by a rebuild of 1947-8, when panels and motifs of nineteenth-century stained glass from West Midlands churches damaged or destroyed in the War were imported. As they represent salvage they cover disparate themes. There are windows from two separate Transfiguration sequences, and moments from other cycles, such as Peter repenting after his denial of Christ, and a feasting scene with a harper who may well be King David.

Stepping into what from the outside is a modest building, the effect of light and colour when you stand at the west end of the nave is remarkable.

There are also windows in the small vestries at the west end of the church which are distinctively different, and particularly appropriate to a rural church as they show farming scenes.

St Peter’s, Drayton

Nestled in a valley, this small church is almost entirely fourteenth century, although the very low west tower apparently dates from 1808. It was also restored in 1877 by Edwin Dolby. From the description, it would be well worth seeing inside, and apparently it is another North Oxfordshire church with the motif of interlocking arms at the head of a capital seen so impressively at Hanwell. There is also an alabaster slab with incised figures commemorating Lewis Granville (d. 1438) and his wife Margaret.

By Elizabeth Knowles

About the Author

Elizabeth Knowles is a renowned library researcher and historical lexicographer who devoted three decades of her career to Oxford University Press. Her time at OUP began with contributions to the OED Supplement and the New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Subsequently, she spearheaded the Quotations publishing program, solidifying her reputation as a leading expert in quotations and lexicography.

In 1999, Knowles assumed the prestigious role of Editor of the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, a position she held continuously until her retirement from OUP in 2007. Under her editorial guidance, the eighth edition was published in 2014, marking a significant milestone in the dictionary’s history.

Knowles is a prolific writer and lecturer on the history of quotations and dictionaries. She has shared her extensive knowledge with both academic and general audiences, significantly enhancing our understanding of the role of quotations in language.

Beyond her work on the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, Knowles is also the editor of “What They Didn’t Say: A Book of Misquotations” (2006) and “How To Read a Word” (2010). Her work continues to inspire and inform scholars, writers, and readers fascinated by the English language.

All photographs © Elizabeth Knowles unless otherwise noted

Churches visited on this route